CLARKSVILLE, TN (CLARKSVILLE NOW) – Spring is transitioning into summer, the masks are coming off and COVID-19 cases are going down. The anticipation of returning of pre-pandemic normalcy is now rife with excitement. But for Gold Star families, Memorial Day is a reminder of a different kind of normal.

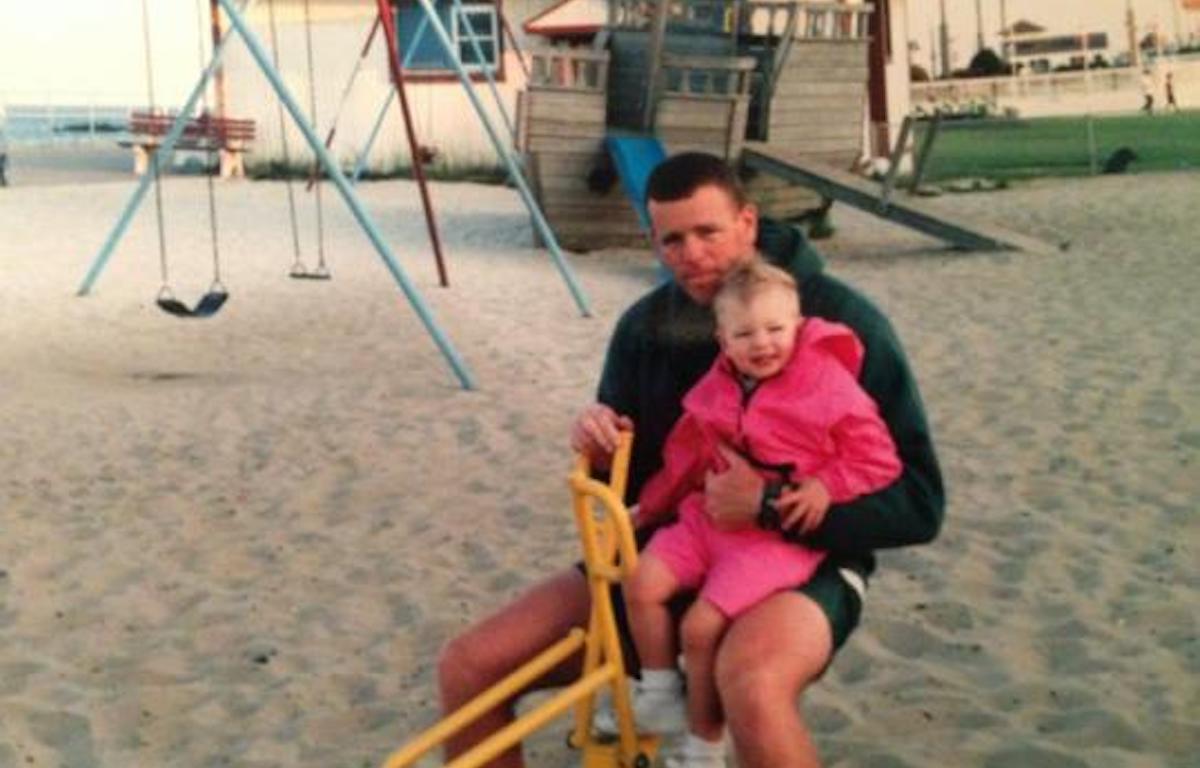

Where others feel excitement about the three-day weekend, I, like so many others, feel a familiar grief. My father, Chief Warrant Officer 3 John A. Quinlan, was killed when his helicopter crashed in Afghanistan on Feb. 18, 2007. I was 10 years old, and ever since, Memorial Day has been personal.

But after a year like the one we’ve just collectively endured, here’s why I think this Memorial Day feels unlike any other.

Lessons learned

I don’t think I’m out of line in saying that the pandemic-induced isolation over the past year forced some major introspection within just about everyone. We lost so, so much; but in contending with the widespread loss of lives, experiences and time with those we love, I think we also gained something: perspective.

And my perspective now is much different than it was years ago, especially when it comes to the loss of my father, what Memorial Day means to me and my relationship with the void he left.

I think his death uniquely equipped me to deal with the pandemic. That probably sounds flippant, but it’s true.

I was only in the 5th grade when he died, and I skipped over the denial stage of the grieving process and went straight to anger. This was especially true when the first Memorial Day after his death rolled around. Everyone around me was going to parties and barbecues, and there I was – sitting at an actual memorial ceremony. I felt isolated. I still feel incredibly isolated because I still resent the fact that I even have to know what Memorial Day is and why it is.

Now, I recognize that my anger and reaction to those celebrations – or to well-meaning “Happy Memorial Day” wishes – was jealousy.

Small reminders

The pandemic also forced me to confront something I had procrastinated on because, frankly, it was painful.

When I was attending Rossview High School, I wanted nothing more than to leave Clarksville. After all, my family was only here because my dad was stationed with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Unit.

I know now that it really was because Clarksville is littered with small reminders of my dad.

I’m reminded of him when I drive down 101st Airborne Division Parkway, past the fields where my father would coach my sister’s recreational soccer teams.

I’m reminded of him when I go downtown, and I hear in my head his geeky, excited tone as he explained his research on the history and museums of yet another town we’d moved to.

I’m reminded of him when I get off Exit 4 and drive past the Sam’s Club, where in the parking lot he asked me five times in a row how my 4th grade science fair project had gone because he was severely concussed and had amnesia after a snowboarding accident.

I’m reminded of him any time I see someone in a military uniform, and with Fort Campbell so close, it’s impossible to avoid.

Because of this, it always felt personally offensive that Memorial Day appeared to be more about the sales, the parties and the unofficial beginning of summer than it ever was about fallen service-members and their families. I felt angry that I had to remember the “real” meaning of this holiday every day while others contained it to a singular weekend.

Forgetting

For the last seven years, I have been removed from Clarksville. I moved to New York City when I turned 19, and in doing so, I got away from those small reminders of the void my dad left in my family.

But the pandemic forced a move back to my family in Clarksville. A move back to where I lost him, where I didn’t have the option to just ignore or avoid those reminders. This is why this Memorial Day is forcing me to really look at why I wanted to forget in the first place.

That his loss is still ever so painful to think about would be the easy answer, but I think it’s because I was truly afraid that no matter what I did, somehow I would never get out from under the weight of that loss.

I think this is a side effect of grief that often goes unspoken. It dominates every aspect of one’s life, and especially when that loss is a service member whose valiance in death is glorified, not just among your community but nationally, it makes it so hard to overcome.

Before the pandemic, I was constantly at war with myself and the role my dad’s death had in my life. I only got to attend my first choice university because of the scholarships I received due to his death. I was afforded amazing opportunities because of that education, like working at Clarksville Now.

Now I recognize that just like in choosing when to remember, I also had autonomy in choosing how I utilized those opportunities.

While everything I have done and will continue to do will be because of my dad’s sacrifice, I realize now it is not everything I am. His death might be the lynchpin in everything I do, but it’s not in everything I accomplish.

Those small reminders now remind me how far I’ve come from where I used to be, and now they don’t hurt so much.

So this Memorial Day, please celebrate. Celebrate the return of normalcy. Celebrate new experiences. Celebrate the time you have with ones you love. Celebrate the small reminders.