CLARKSVILLE, TN (CLARKSVILLE NOW) – Leadership is never easy. Putting yourself out there at the risk of public criticism, insult or failure can be uncomfortable. But when you’re Black – particularly during the Jim Crow or civil rights era in the South – those risks go well beyond discomfort. This year, in honor of Black History Month, let’s look back at not just at the “firsts” in local history, and not just at athletes and artists, but to leaders who took the risks and rose to the top to make Clarksville a better place for everyone.

Here are 10 Black leaders (in alphabetical order) who during their lifetimes helped to shape our community and deserve to be remembered for their role in Clarksville history.

1. Geneva Bell

Uncovered Mount Olive Cemetery

For several years in Clarksville, Genevia (“Geneva”) Ann Bell was a one-woman whirlwind of advocacy and altruism. In 2001, when she was 60 years old, just a year after getting her GED, Bell was taking a history class at Austin Peay State University and learned out about Mount Olive Cemetery. She went to visit the Black cemetery off of Rollins Drive and was shocked to find it covered in debris and garbage, having been largely ignored and forgotten for decades. It contains more than 1,300 graves, some dating to the early 1800s. Among those buried there are freed slaves and 25 Black Civil War soldiers. Bell founded the Mount Olive Cemetery Historical Preservation Society and solicited help over the years from Austin Peay State University, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ROTC groups and more. The cemetery is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bell moved to Clarksville in the 19990s from California, where she was active in 4-H programs and efforts to help at-risk youth. As early as 1998, Bell organized annual Make A Difference Day events in Clarksville with projects organized around a new community garden, health fairs, grandparent support, bone marrow donation and more. In 2007, Bell was honored with a $10,000 grant from USA Weekend magazine for a Make a Difference Day event that created scholarships to help people get their GED. Bell died Sept. 25, 2018, at the age of 77. She is remembered in a historic marker at Mount Olive Cemetery.

2. General Quarles Boyd

Ground-breaking attorney, early Republican leader

General Quarles (G.Q.) Boyd, born in 1865 with the first name “General,” was the first black attorney in Montgomery County and a leader in early efforts to organize Black political power. He attended Wilberforce University and then studied at the Tennessee Supreme Court in the office of Justice Horace Lurton, and locally in the office of Cave Johnson. He appears to have started his local law practice in the early 1890s. Not long after, Boyd became leader of the local Republican Party, standing up candidates for county office and being nominated to run for Congress. On Aug. 23, 1897, at only 32 years old, he was murdered by someone with a personal grudge. He was remembered in an otherwise hostile Leaf-Chronicle editorial as having “attained more prominence than any of his race has ever attained in this county.” Just days after his death, he had been scheduled to speak at the Nashville Centennial, where he was remembered as one of the best lawyers in Tennessee.

Today, Boyd is memorialized in the name of the General Q. Boyd Elks Lodge 457, the name of the Montgomery County Court Center’s Bar Association Room and in the cornerstone of St. Peter’s AME Church.

3. Susie Brown

Education leader, community advocate

Susie A. Brown (later Susie Brown Farrar Tucker), born in the Rossview area, was an educator for 35 years, with 23 of those as Montgomery County’s first supervisor for Black county schools, a position she held in 1919. During the 1920s, Brown worked tirelessly to ensure strong education for rural children. In early years of her work, she would often ride by horse and buggy to visit rural schools, though in later years she was driven out by car with a hired driver. She attended national conferences and brought back new training for her teachers, and she encouraged them to enroll in special summer college courses to improve their skills. She also organized annual arts and craft exhibits at the county courthouse for a two-day display, reviewed by the school board.

In addition to her leadership in the schools, Brown led the local Better Homes movement, an initiative to repair and restore older homes in Black neighborhoods. She was also choir director for St. Peter AME Church. She died Sept. 3, 1947.

4. Dr. Robert Burt

Pioneering doctor, hospital founder

Dr. Robert Tecumseh Burt was born in Mississippi in 1873. He started as a teacher, then enrolled at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, graduating in 1897. He opened his first office in McMinnville, then in 1904, he relocated to Clarksville to set up a medical practice on Third Street. In the beginning of his career, he only served Black patients, but in time he opened his practice to patients of all races. In 1906, Burt opened Clarksville’s first hospital, The Home Infirmary, near what is now Riverside Drive. Burt operated his hospital until Clarksville Memorial Hospital opened in 1954, just one year before he died in 1955.

Today, Clarksville honors Burt’s memory in the names of the old Burt High School, now Burt Elementary, and the city’s Burt-Cobb Recreation Center, as well as in an exhibit at the Customs House Museum and Cultural Center.

5. Wilbur Daniel

Paved way for APSU integration, NAACP leader

Wilbur N. Daniel’s time in Clarksville was brief, but it had major significance, as he was the first Black graduate of Austin Peay State University.

Daniel was born on Jan. 2, 1918, in Louisville, Kentucky, and he entered the ministry at the age of 25. After serving at churches in Indiana and Nashville, in 1949 he accepted the pastorate of the St. John Baptist Church in Clarksville. While here, he applied for admittance to Austin Peay State College, which up to that time was all white. Daniel graduated with honors in 1957 receiving the Master of Arts degree.

In 1957, Daniel became pastor of Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in Chicago. In the mid 1960’s, under Daniel’s leadership, Antioch played a key role in partnering with the government to provide affordable public housing. Among many other roles in state and national boards, he served as president of the Chicago Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for two years.

The Wilbur N. Daniel African American Cultural Center at Austin Peay University was named in his honor in December 1992.

6. Jesse M.H. Graham

First local Black legislator, American Legion post founder

Jesse M.H. Graham was elected in early November 1896 to represent Montgomery County as a Republican in the Tennessee General Assembly. He was not only the first Black person chosen to represent Montgomery County, but also the first Republican representative elected in that district since Reconstruction – reportedly by “the largest vote ever cast for a legislative candidate” in the county. But just after the election, the Louisville Courier-Journal reported that Graham had lived in Louisville until October 1895. His opponent promptly called attention to the three-year residency requirement and challenged Graham’s eligibility to hold office. On Jan. 20, 1897, the General Assembly passed a resolution declaring the seat vacant. No other Black candidates were elected to the General Assembly until 1964.

Graham was born in Middle Tennessee and attended public schools in Montgomery and Davidson counties and then as a Peabody scholar attended Fisk University. After graduating from Fisk, Graham evidently taught school for some time in Clarksville and Kentucky and ran a saloon at 97 Strawberry St. Around 1892, he moved to Louisville and became a clerk at the post office. After three years, Graham returned to Clarksville, where he took over the editorship of the Clarksville Enterprise and then was elected to state office.

Graham may have served in the Spanish American War. At some point before World War I. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army in October 1917. Honorably discharged at war’s end, Graham returned to Clarksville, where he served as an officer of St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Church and helped found American Legion Post No. 143. He died July 25, 1930, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

7. J.A. Jackson

Led community efforts after Great Fire of 1878

Coming out of the Reconstruction era was a tumultuous time for the entire South, and Clarksville was no exception. When disputes arose – one dramatic one in particular – Clarksville turned to a key Black leader to help resolve them: J.A. Jackson.

In the spring of 1878, there had been a series of racially charged incidents, including the lynching of a Black landowner. In the wake of this, on the night of April 13, an unarmed Black man named Columbus Seat was shot and killed during a skirmish with a Clarksville Police officer. A crowd of protesters gathered outside the police station demanding justice, and during that gathering, a fire started downtown. It would later be known as the Great Fire of 1878, which destroyed much of downtown Clarksville.

Newspaper reports at the time blamed the crowd and demanded arrests. In an effort to calm things down on both sides, city leaders convened a public meeting of Black and white citizens, and Jackson was called upon as one of the speakers. Not a lot of historical documentation is available about Jackson, but he was described as a school teacher and a frequent candidate for city alderman. In his speech, Jackson said that Black people were being misrepresented – that there were lawless whites and lawless Blacks, “but that respectable men of both races condemned them and wanted them punished by due process of law,” according to the Clarksville Tobacco Leaf. Jackson was one of three Black leaders appointed to a 10-member investigative committee to look into the cause of the fire.

Ultimately, their efforts ended in silence. But there were no arrests or further public violence from either side, thanks in part to Jackson’s leadership.

8. Pastor Jerry Jerkins

Led protests for racial justice

The longtime pastor of St. John Missionary Baptist Church and civil rights activist was instrumental in getting a portion of Highway 76 renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Parkway, getting Guthrie Highway renamed Wilma Rudolph Boulevard, and establishing the Wilbur N. Daniel African American Center at Austin Peay State University.

Born on Sept. 21, 1932, in Loxley, Alabama, Jerkins came to the area after being stationed at Fort Campbell. He became pastor of St. John Missionary Baptist Church in 1967. He was president of the NAACP’s Clarksville branch for 20 years, and during his presidency, he led several protests for racial justice in Clarksville. He also served on the Tennessee Title IV Commission, on APSU’s advisory board, and as president of the Tennessee Missionary Baptist State Convention. Jerkins died Aug. 28, 2021.

In September 2022, Kraft Street was dedicated Pastor Jerry G. Jerkins Memorial Highway.

9. Wilma Rudolph

Forced Clarksville’s first integrated public event

Wilma Rudolph, born June 23, 1940, in St. Bethlehem, faced misfortune from an early age, being diagnosed with polio and told she would never walk again. She beat those odds and ended up being a basketball star at Burt High School, then excelled at track at Tennessee State University. Her success led her to qualify for her first Olympics in 1956. She competed in the 4×100 relay in Melbourne, Australia, and won bronze. Rudolph’s dominance in track continued in the Rome Olympics in 1960. This time she won three gold medals and broke three world records. She became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track and field at a single Olympics.

Most importantly for Clarksville’s history, after the Olympics she refused to attend her own homecoming parade unless the event was integrated. Rudolph’s actions led to the first fully integrated event in Clarksville.

Rudolph died Nov. 12, 1994. Her name carries on in Wilma Rudolph Boulevard, dedicated to her in 1994. A life-sized bronze statue of Wilma Rudolph has been placed at the Wilma Rudolph Event Center at Liberty Park.

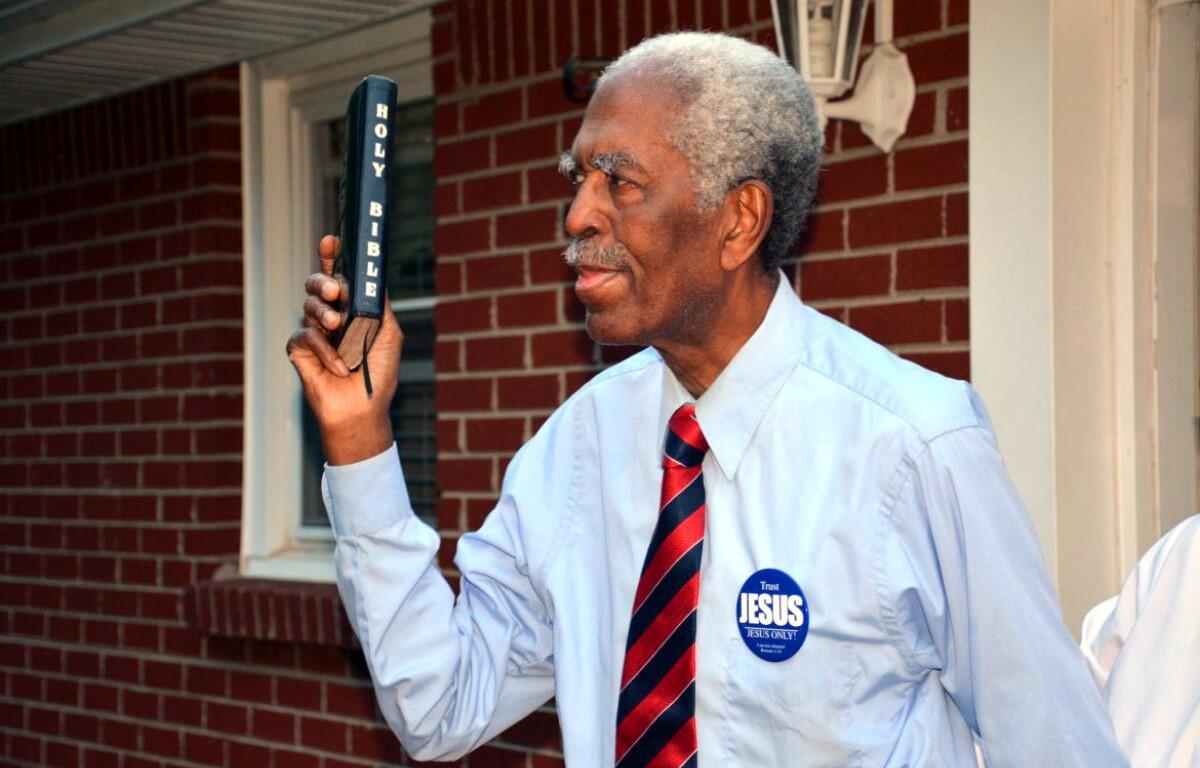

10. Pastor Jimmy Terry Sr.

Founded Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church and School

The Rev. Jimmy Terry Sr. was a skillful preacher and founder of Tabernacle Christian School who touched generations of Clarksvillians through his ministry and community leadership. He was well-known for his annual campaigns to “Jesus is the reason for the season” and “Easter is all about Jesus” and for his saying, “Clarksville is a great place to live.”

Terry was born July 22, 1937, and was raised in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. He served in the Navy. He was founder and pastor of Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church on Market Street, and he and his wife, Servella Terry, founded Tabernacle Christian School in 1999. He petitioned the state to rename Highway 79, formerly Guthrie Highway, to Wilma Rudolph Boulevard, and he helped establish a committee to commission a statue in her honor, which is now located at the Wilma Rudolph Event Center at Liberty Park. Terry was a member of the first class of Leadership Clarksville in 1987. He was an original director of Legends Bank and served on the Clarksville Chamber of Commerce Board of Directors.

He died on June 21, 2017. He is memorialized in the Jimmy Terry Monument at McGregor Park, dedicated in February 2019, and a portion of Providence Boulevard as Pastor Jimmy Terry Sr. Memorial Highway.

Keep it going

This is only a brief overview of readily available historical research. Much more work needs to be done, particularly on lesser-known leaders like Susie Brown and J.A. Jackson. Clarksville has a rich history, and so much more could be done to uncover the Black history of our community. Let’s strive to make sure these stories are uncovered so they can be told for years to come.

Sources: Clarksville Now and Leaf-Chronicle archives, Austin Peay State University, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Historic Clarksville 1784-2004, Visit Clarksville, family obituaries, and historical research published by Richard P. Gildrie, Lorenza Collier, Carolyn Ferrell and Phil Petrie.